Alcoholism

Highlights

Do You Have a Drinking Problem?

You may be experiencing symptoms of alcohol abuse (problem drinking) or alcohol dependence (alcoholism) if you:

- Have little or no control over the amount you drink, when you drink, or how often you drink.

- Tried to limit or stop your drinking but found you couldn’t.

- Had withdrawal symptoms when you tried to stop drinking. (These symptoms include tremors, anxiety, irritability, racing heart, nausea, sweating, trouble sleeping, and seizures.)

- Have put yourself in a dangerous situation (such as driving, swimming, and unsafe sex) on one or more occasions while drinking.

- Have become tolerant to the effects of drinking and require more alcohol to become intoxicated.

- Have continued to drink despite having memory blackouts after drinking or having frequent hangovers that cause you to miss work and other normal activities.

- Have continued to drink despite having a medical condition that you know is worsened by alcohol consumption.

- Have continued to drink despite knowing it is causing problems at home, school, or work.

- Drink alone or start your drinking early in the day.

Screening Tests

There are many screening tests that doctors use to check for alcohol use disorders. Some of these tests you can take on your own. The CAGE test is an acronym for the following questions. It asks:

- Have you ever felt you should CUT (C) down on your drinking?

- Have people ANNOYED (A) you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or GUILTY (G) about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning, to steady your nerves, or to get rid of a hangover [use of alcohol as an EYE-OPENER (E) in the morning].

- If you responded “yes” to at least two of these questions, you may be at risk for alcoholism.

Introduction

Alcohol use disorders refer to excessive drinking behaviors that can create dangerous conditions for an individual and others. Alcohol use disorders are generally categorized as:

Alcohol Abuse. Alcohol abuse is a pattern of drinking that results in adverse outcomes such as:

- Failure to fulfill work or personal obligations

- Recurrent use of alcohol in potentially dangerous situations

- Problems with the law

- Continued use in spite of harm being done to social or personal relationships

Alcohol use can lead to alcohol dependence (alcoholism).

Alcohol Dependence (Alcoholism). Alcohol dependence is the medical term for alcoholism. Alcohol dependence is characterized by:

- Increased amounts of alcohol are needed to produce an effect (tolerance)

- Withdrawal symptoms (nausea, sweating, irritability, tremors, hallucinations, and seizures) develop when drinking is stopped or reduced

- Constant craving for alcohol and inability to limit drinking

- Continuing to drink in spite of the knowledge of its physical or psychological harm to oneself or others

Levels of Drinking

A person is affected by the amount of alcohol consumed, not the type. Beer and wine are not “safer” than hard liquor; they simply contain less alcohol per ounce.

The following drinking categories use a definition of “one drink” as 12 ounces of beer, 8 - 9 ounces of malt liquor, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces (a jigger or shot) of 80-proof liquor. Therefore, 12 ounces of beer is equivalent to 5 ounces of wine, or a 1.5 ounce shot of hard liquor.

Moderate Drinking. Moderate drinking may possibly decrease the risk of heart disease when it is part of other heart-healthy behaviors. However, even small amounts of alcohol should be avoided in certain circumstances, such as before driving a vehicle or operating machinery, during pregnancy, when taking medications that may interact with alcohol, or if you have a medical condition that may be worsened by drinking.

Moderate drinking is defined as:

- No more than two drinks a day for men and one drink a day for women.

Low-Risk Drinking. Low-risk drinking is defined as:

- No more than 4 drinks in a day, or 14 drinks per week, for men

- No more than 3 drinks in a day, or 7 drinks per week, for women (both men and women over age 65 are advised not to drink more than this amount)

At-Risk (Heavy) Drinking. At-risk (heavy) drinking is defined as:

- More than 14 drinks per week, or four drinks in a day, for men

- More than seven drinks per week, or three drinks in a day, for women

Risk Level Assessment. According to the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), people who consume alcohol are considered:

- At low risk for alcohol-related problems if they always drink within low-risk limits

- At increased risk if they drink more than either the single-day limits or the weekly limits

- At highest risk if they drink more than both the single-day limits and the weekly limits

Certain people are at much higher risk for harmful effects of alcohol, such as older individuals with high blood pressure or those taking medications for anxiety, arthritis, or pain.

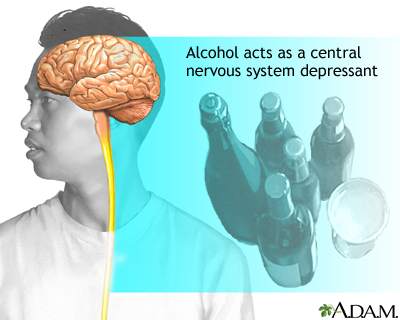

Causes

The chemistry of alcohol allows it to affect nearly every type of cell in the body, including those in the central nervous system. After prolonged exposure to alcohol, the brain becomes dependent on it. Drinking steadily and consistently over time can produce dependence and cause withdrawal symptoms during periods of abstinence. This physical dependence, however, is not the sole cause of alcoholism. To develop alcoholism, other factors usually come into play, including biology, genetics, culture, and psychology.

Genetic Factors

Genetic factors appear to play a significant role in alcoholism and may account for about half of the total risk for alcoholism. The role that genetics plays in alcoholism is complex and it is likely that many different genes are involved. Research suggests that alcohol dependence, and other substance addictions, may be associated with genetic variations in more than 50 different chromosomal regions. Inherited traits that may indicate a possible but unproven association with alcoholism include.

- The amygdala, an area of the brain thought to play a role in the emotional aspects of craving, has been reported to be smaller in subjects with family histories of alcoholism.

- People may inherit a lack of the warning signals that ordinarily make people stop drinking. Even in the absence of genetic factors, repeated exposure to alcohol increases the ability to tolerate larger amounts before experiencing behavioral impairment.

- Serotonin is a brain chemical messenger (neurotransmitter). It is important for well-being and associated behaviors (eating, relaxation, and sleep). Abnormal serotonin levels are associated with high levels of tolerance for alcohol.

- Dopamine is another neurotransmitter associated with alcoholism and other addictions. High levels of the D2 dopamine receptor may help inhibit behavioral responses to alcohol, and protect against alcoholism, in people with a family history of alcohol dependence.

Even if genetic factors can be identified, they are unlikely to explain all cases of alcoholism. It is important to understand that whether they inherit the disorder or not, people with alcoholism are still legally responsible for their actions. Inheriting genetic traits does not doom a child to an alcoholic future. Environment, personality, and emotional factors also play a strong role.

Brain Chemical Imbalances after Long-Term Alcohol Use

Alcohol has widespread effects on the brain and can affect neurons (nerve cells), brain chemistry, and blood flow within the frontal lobes of the brain. Neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain) are affected by long-term use of alcohol.

When a person who is dependent on alcohol stops drinking, chemical responses create an overexcited nervous system and agitation by changing the level of chemicals that inhibit impulsivity or stress and excitation. High levels of norepinephrine, a chemical in the body that increases when drinking is stopped, may trigger withdrawal symptoms such as rising blood pressure and heart rate. Hyperactivity in the brain produces an intense need to calm down and to use more alcohol.

Alcohol also stimulates the release of other neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, and opioid peptides) that produce pleasurable feelings such as euphoria, a sensation of being rewarded, and a sense of well-being.

Over time, however, heavy alcohol use appears to deplete the stores of dopamine and serotonin. Persistent drinking eventually fails to restore mood, but by then the drinker has been conditioned to believe that alcohol will improve spirits (even though it does not).

Social and Emotional Causes of Alcoholic Relapse

Most people treated for alcoholism relapse, even after years of abstinence. Patients and their caregivers should understand that relapses of alcoholism are comparable to recurrent flare-ups of chronic physical diseases. Factors that place a person at high risk for relapse include:

- Frustration and anger

- Social pressure

- Internal temptation

Mental and Emotional Stress. Alcohol blocks out emotional pain and is often perceived as a loyal friend when human relationships fail. It is also associated with freedom and with a loss of inhibition that offsets the tedium of daily routines. When the alcoholic tries to quit drinking, the brain seeks to restore what it perceives to be its equilibrium. The brain responds with depression, anxiety, and stress (the emotional equivalents of physical pain), which are produced by brain chemical imbalances. These negative moods continue to tempt patients to return to drinking long after physical withdrawal symptoms have resolved.

Codependency. Many aspects of the ex-drinker's relationships change when drinking stops, making it difficult to remain abstinent:

- One of the most difficult problems that occur is being around other people who are able to drink socially without danger of addiction. This can lead to loneliness, low self-esteem, and a strong desire to drink again.

- Friends may not easily accept the sober, perhaps more subdued, ex-drinker. Close friends and even intimate partners may have difficulty in changing their responses to this newly sober person and, even worse, may encourage a return to drinking.

- To preserve marriages, spouses of alcoholics often build their own self-images on surviving or handling their mates' difficult behavior and then discover that they find it difficult to adjust to new roles and behaviors.

In order to maintain abstinence, the ex-drinker may need to separate from these "enablers." Close friends and family members can find help in understanding and dealing with these issues through groups such as Al-Anon.

Social and Cultural Pressures. The media portrays the pleasures of drinking in advertising and programming. The medical benefits of light-to-moderate drinking are frequently publicized, giving ex-drinkers the invalid excuse of returning to alcohol for their health.

Risk Factors

According to the U.S. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, about 70% of American adults always drink at low-risk levels or do not drink at all. (Thirty-five percent of Americans do not consume alcohol.) About 28% of American adults drink at levels that put them at risk for alcohol dependence and alcohol-related problems.

Risk factors for alcohol dependence include:

Age

Drinking in Adolescence. About half of under-age Americans have used alcohol. About 2 million people ages 12 - 20 are considered heavy drinkers, and 4.4 million are binge drinkers. Anyone who begins drinking in adolescence is at risk for developing alcoholism. The earlier a person begins drinking, the greater the risk.

Young people at highest risk for early drinking are those with a history of abuse, family violence, depression, and stressful life events. People with a family history of alcoholism are also more likely to begin drinking before the age of 20 and to become alcoholic. Such adolescent drinkers are also more apt to underestimate the effects of drinking and to make judgment errors, such as going on binges or driving after drinking, than young drinkers without a family history of alcoholism.

Drinking in the Elderly Population. Although alcoholism usually develops in early adulthood, the elderly are not exempt. In fact, doctors may overlook alcoholism when evaluating elderly patients, mistakenly attributing the signs of alcohol abuse to the normal effects of the aging process.

Alcohol also affects the older body differently. People who maintain the same drinking patterns as they age can easily develop alcohol dependency without realizing it. It takes fewer drinks to become intoxicated, and older organs can be damaged by smaller amounts of alcohol than those of younger people. Also, many of the medications prescribed for older people interact adversely with alcohol. Medications used for arthritis or pain pose a particular danger for interaction with alcohol.

Gender

A majority of alcoholics are men, but the incidence of alcoholism in women has been increasing over the past 30 years. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, about 17% of men and 8% of women meet criteria for alcohol dependence at some point in their lives. Studies suggest that women are more vulnerable than men to many of the long-term consequences of alcoholism. For example, women are more likely than men to develop alcoholic hepatitis and to die from cirrhosis, and women are more vulnerable to the brain cell damage caused by alcohol.

History of Abuse

Individuals who were physically or sexually abused as children have a higher risk for substance abuse later in life. They may also have poorer responses to treatment than those without such a history.

Race and Ethnicity

Overall, there is no difference in alcoholic prevalence among African-Americans, Caucasians, and Hispanic-Americans. Some population groups, however, such as Native Americans, have an increased incidence of alcoholism while others, such as Jewish and Asian Americans, have a lower risk. Although the biological or cultural causes of such different risks are not known, certain people in these population groups may have a genetic susceptibility or invulnerability to alcoholism because of the way they metabolize alcohol.

Psychiatric and Behavioral Disorders

Psychiatric Disorders. Severely depressed or anxious people are at high risk for alcoholism, smoking, and other forms of addiction. Likewise, a large proportion of alcohol-dependent people suffer from an accompanying psychiatric or substance abuse disorder. Either anxiety or depression may increase the risk for self-medication with alcohol. Depression is the most common psychiatric problem in people with alcoholism or substance abuse and studies suggest that alcohol use may increase the risk for depression. Alcohol abuse is very common in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Specific anxiety disorders, such as panic disorders and social phobia, may pose particular risks for alcohol and substance abuse. Social phobia causes an intense fear of being publicly scrutinized and humiliated. Panic disorders cause intense anxiety and panic attacks. People with these disorders may use alcohol as a way to become less inhibited in public situations or to calm feelings of panic. People who have anxiety disorders are more likely to resume drinking after treatment for alcohol dependence. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #28: Anxiety.]

Long-term alcoholism itself may cause chemical changes that produce anxiety and depression. It is not always clear whether people with emotional disorders are self-medicating with alcohol, or whether alcohol itself is producing mood swings. For patients who have both alcoholism and major depression, doctors recommend first treating the alcohol use disorder because abstinence from alcohol may help resolve the depression.

Behavioral Disorders and Lack of Impulse Control. Studies indicate that alcoholism is strongly related to impulsive, excitable, and novelty-seeking behavior, and such patterns are established early on. Specifically, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a condition that shares these behaviors, have a higher risk for alcoholism in adulthood. The risk is especially high in children with ADHD and conduct disorder.

Socioeconomic Factors

Alcoholism is not restricted to any specific socioeconomic group or class.

Complications

Alcoholism reduces life expectancy by about 10 - 12 years. The earlier people begin drinking heavily, the greater their chance of developing serious illnesses later on.

Alcoholism and Early Death

Alcohol can affect the body in so many ways that researchers have a hard time determining exactly what the consequences are from drinking. Heavy drinking is associated with earlier death. However, it is not just from a higher risk of the more common serious health problems, such as heart attack, heart failure, diabetes, lung disease, or stroke. Chronic alcohol consumption leads to many problems that can increase the risk for death:

- People who drink regularly have a higher rate of death from injury or violence.

- Alcohol overdose can lead to death. This is a particular danger for adolescents who may want to impress their friends with their ability to drink alcohol but cannot yet gauge its effects. However, alcohol overdose doesn't only occur from any one heavy drinking incident, but may also occur from a constant infusion of alcohol in the bloodstream.

- Severe withdrawal and delirium tremens. Delirium tremens is a very serious form of alcohol withdrawal with symptoms that involve mental and nervous system changes. In some cases, it can be fatal.

- Frequent, heavy alcohol use directly harms many areas in the body and produce dangerous health conditions (liver damage, pancreatitis, anemia, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, nerve damage, and erectile dysfunction).

- Alcohol abusers who need surgery have an increased risk of postoperative complications, including infections, bleeding, insufficient heart and lung functions, and problems with wound healing. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms after surgery may impose further stress on the patient and hinder recuperation.

Liver Disorders

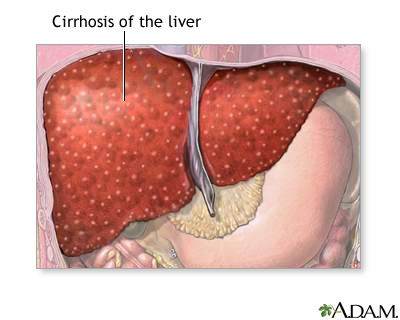

Alcohol-Induced Liver Disease. Alcohol-induced liver disease (also called alcoholic liver disease) is a spectrum of liver disorders caused by excessive alcohol consumption. Alcohol-induced liver disease includes:

- Fatty liver

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Alcoholic cirrhosis

Alcohol is absorbed in the small intestine and passes directly into the liver, where it becomes the preferred energy source. The liver is particularly endangered by alcoholism. In the liver, alcohol converts to toxic chemicals, notably acetaldehyde, which trigger the production of immune factors called cytokines. In large amounts, these factors cause inflammation and tissue injury.

Fatty liver is an accumulation of fat inside liver cells. It is the most common type of alcohol-induced liver disease and can occur even with moderate drinking. Symptoms include an enlarged liver with pain in the upper right quarter of the abdomen. Fatty liver can be reversed once the patient stops drinking. Fatty liver can also develop without exposure to alcohol, especially in people who are obese or have type 2 diabetes.

Alcoholic hepatitis is inflammation of the liver that develops from heavy drinking. Symptoms include fever, jaundice (yellowing of the skin), right-side abdominal pain, fatigue, and nausea and vomiting. Mild cases may not produce symptoms. Patients who are diagnosed with alcoholic hepatitis must stop drinking. Patients who continue to drink may go on to develop cirrhosis and liver failure.

Between 10 - 20% of people who drink heavily (five or more drinks a day) develop cirrhosis, a progressive and irreversible scarring of the liver that can eventually be fatal. Alcoholic cirrhosis (also sometimes referred to as portal, Laennec’s, nutritional, or micronodular cirrhosis) is the primary cause of cirrhosis in the U.S. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Not eating when drinking and consuming a variety of alcoholic beverages increase the risk for liver damage. Obesity also increases the risk for all stages of liver disease.

Hepatitis B and C. People with alcoholism may have lifestyles that put them at higher risk for hepatitis B and C. Chronic forms of viral hepatitis pose risks for cirrhosis and liver cancer, and alcoholism significantly increases these risks. People with alcoholism should be immunized against hepatitis B. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #59: Hepatitis.]

Gastrointestinal Problems

Alcoholism can cause many problems in the gastrointestinal tract. Violent vomiting can produce tears in the junction between the stomach and esophagus. It increases the risk for ulcers, particularly in people taking the painkillers known as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin or ibuprofen. It can also lead to swollen veins in the esophagus, (called varices), and to inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) and bleeding.

Alcohol can contribute to serious acute and chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) in people who are susceptible to this condition. There is some evidence of a higher risk for pancreatic cancer in people with alcoholism, although this higher risk may occur mainly in people who are also smokers.

Effect on Heart Disease and Stroke

Moderate amounts (one to two drinks a day) of alcohol can improve some heart disease risk factors, such as increasing HDL (“good cholesterol”) levels. However, at this time there is no definitive proof that moderate drinking improves overall health, and the American Heart Association does not recommend drinking alcoholic beverages solely to reduce cardiovascular risk.

Excessive drinking clearly has negative effects on heart health. Alcohol is a toxin that damages the heart muscle. In fact, heart disease is one of the leading causes of death for alcoholics. Alcohol abuse increases levels of triglycerides (unhealthy fats) and increases the risks for high blood pressure, heart failure, and stroke. In addition, the extra calories in alcohol can contribute to obesity, a major risk factor for many heart problems.

Cancer

Alcohol abuse and dependence may increase the risk for certain type of cancers. In particular, heavy alcohol use appears to increase the risks for mouth, throat, esophageal, gastrointestinal, liver, and colorectal, cancers. Even moderate drinking can increase the risk of breast cancer. Although the additional risk is small, women who are at high risk for breast cancer should consider not drinking at all.

Effects on the Lungs

Pneumonia. Over time, chronic alcoholism can cause severe reductions in white blood cells, which increase the risk for pneumonia. Patients who are alcohol dependent should get an annual pneumococcal pneumonia vaccination. The initial signs of pneumococcal pneumonia are high fever and cough, sometimes with stabbing chest pains. Contact your doctor immediately if you experience these symptoms.

Skin, Muscle, and Bone Disorders

Severe alcoholism is associated with osteoporosis (loss of bone density), muscular deterioration, skin sores, and itching. Alcohol-dependent women seem to face a higher risk than men for damage to muscles, including muscles of the heart, from the toxic effects of alcohol.

Effects on Reproduction and Fetal Development

Sexual Function and Fertility. Alcoholism increases levels of the female hormone estrogen and reduces levels of the male hormone testosterone, factors that possibly contribute to erectile dysfunction and enlarged breasts in men, and infertility in women. Such changes may also be responsible for the higher risks for absent periods and abnormal uterine bleeding in women with alcoholism.

Drinking During Pregnancy and Effects on the Infant. Even moderate amounts of alcohol can have damaging effects on the developing fetus, including low birth weight and an increased risk for miscarriage. High amounts can cause fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition that can cause mental and growth retardation. Although there is no specific amount of alcohol intake, the risk of developing the syndrome is increased depending on when alcohol exposure occurs during pregnancy, the pattern of drinking (four or more drinks per occasion), and how often alcohol consumption occurs.

Effect on Weight and Diabetes

Moderate alcohol consumption may help protect the hearts of adults with type 2 diabetes. Heavy drinking, however, is associated with obesity, which is a risk factor for this form of diabetes. In addition, alcohol can cause hypoglycemia, a drop in blood sugar, which is especially dangerous for people with diabetes who are taking insulin. Intoxicated diabetics may not be able to recognize symptoms of hypoglycemia.

Effect on Central and Peripheral Nervous System and Mental Functioning

Drinking too much alcohol can cause immediate mild neurologic problems in anyone, including insomnia and headache. Long-term alcohol use can physically affect the brain. Depending on length and severity of alcohol abuse, neurologic damage may not be permanent, and abstinence nearly always leads to eventual recovery of normal mental function.

Effect on Mental Functioning. Recent high alcohol use (within the last 3 months) is associated with some loss of verbal memory and slower reaction times. Over time, chronic alcohol abuse can impair so-called "executive functions," which include problem solving, mental flexibility, short-term memory, and attention. These problems are usually mild to moderate and can last for weeks or even years after a person quits drinking. In fact, such persistent problems in judgment are possibly one reason for the difficulty in quitting. Alcoholic patients who have co-existing psychiatric or neurologic problems are at particular risk for mental confusion and depression.

Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

People who are alcohol dependent should be sure to take vitamin and mineral supplements. Even apparently well-nourished people with alcoholism may be deficient in important nutrients. Deficiencies in vitamin B pose particular health risks. Other vitamin and mineral deficiencies, however, can also cause widespread health problems.

Folate Deficiencies. Alcohol interferes with the metabolism of folate, a very important B vitamin, called folic acid when used as a supplement. Folate deficiencies can cause severe anemia. Deficiencies during pregnancy can lead to birth defects in the infant.

Wernicke-Korsakoff Syndrome. Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome is a serious consequence of severe thiamin (vitamin B1) deficiency. Symptoms of this syndrome include severe loss of balance, confusion, and memory loss. Eventually, it can result in permanent brain damage and death. Once the syndrome develops, oral supplements have no effect, and only a rapid infusion of intravenous vitamin B1 can treat this serious condition.

Peripheral Neuropathy. Vitamin B12 deficiencies can also lead to peripheral neuropathy, a condition that causes pain, tingling, and other abnormal sensations in the arms and legs.

Drug Interactions

The effects of many medications are strengthened by alcohol, while others are inhibited. Of particular importance is alcohol's reinforcing effect on anti-anxiety drugs, sedatives, antidepressants, and antipsychotic medications.

Alcohol also interacts with many drugs used by people with diabetes. It interferes with drugs that prevent seizures or blood clotting. It increases the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding in people taking aspirin or other nonsteroidal inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen and naproxen.

Chronic alcohol abusers have a particularly high risk for adverse side effects from consuming alcohol while taking certain antibiotics. These side effects include flushing, headache, nausea, and vomiting. In other words, taking almost any medication should preclude drinking alcohol.

Increased Risk for Other Addictions

Researchers are finding common genetic factors in alcohol and nicotine addiction, which may explain, in part, why alcoholics are often smokers. Alcoholics who smoke compound their health problems. In fact, some studies indicate that people who are alcohol-dependent and smoke are more likely to die of smoking-related illnesses than alcohol-related conditions. Abuse of other drugs is also common among alcoholics.

Accidents, Suicide, and Murder

Alcohol plays a large role in accidents, suicide, and crime:

- Alcohol plays a major role in more than half of all automobile fatalities.

- Alcohol-related automobile accidents are one of the leading causes of death in young people.

- Fewer than two drinks can impair the ability to drive. Even one drink may double the risk of injury, and more than four drinks increases the risk by 11 times.

- Alcoholism is the primary diagnosis in a quarter of all people who commit suicide.

- Alcohol is implicated in over half of all murders.

Domestic Violence

Alcoholic households are less cohesive and have more conflicts, and their members are less independent and expressive than households with nonalcoholic or recovering alcoholic parents. Domestic violence is a common consequence of alcohol abuse.

Effect on Women. A serious risk factor for injury from domestic violence may be a history of alcohol abuse in the male partner.

Effect on Children. Alcoholism in parents also increases the risk for violent behavior and abuse toward children. Children of alcoholics tend to do worse academically than others, and have a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and stress and lower self-esteem than their peers. In addition to their own inherited risk for later alcoholism, many children of alcoholics have serious coping problems that may last their entire life.

Adult children of alcoholic parents are at higher risk for divorce and for psychiatric symptoms. One study concluded that the only events with greater psychological impact on children are sexual and physical abuse.

The Effects of Hangover

Although not traditionally thought of as a medical problem, hangovers have significant consequences. Hangovers can impair job performance, increasing the risk for mistakes and accidents. Hangovers are generally more common in light-to-moderate drinkers than heavy and chronic drinkers, suggesting that binge drinking can be as threatening as chronic drinking. Any man who drinks more than five drinks or any woman who has more than three drinks at one time is at risk for a hangover.

Symptoms

You may be experiencing symptoms of alcohol abuse or dependence if you:

- Have little or no control over the quantity you drink or the duration or frequency of your drinking

- Tried to limit or stop your drinking but found you couldn’t

- Had withdrawal symptoms when you tried to stop drinking. (These symptoms include tremors, anxiety, irritability, racing heart, nausea, sweating, trouble sleeping, and seizures.)

- Have had one or more occasion when you put yourself in a dangerous situation (such as driving, swimming, or unsafe sex) while drinking

- Have become tolerant to the effects of drinking and require more alcohol to become intoxicated (the idea of being able to “hold your liquor" is an illusion)

- Have continued to drink despite having memory blackouts after drinking or having frequent hangovers that cause you to miss work and other normal activities

- Have continued to drink despite having a medical condition that you know is worsened by alcohol consumption

- Have continued to drink despite you know it is causing problems at home, school, or work

- Drink alone or start your drinking early in the day

- Have a history of legal problems caused by your drinking

Alcohol use disorders can develop insidiously, and often there is no clear line between alcohol abuse (problem drinking) and alcohol dependence (alcoholism). Eventually alcohol dominates thinking, emotions, and actions and becomes the primary means through which a person can deal with people, work, and life.

Diagnosis

Sometimes a person can recognize that alcohol is causing problems, and will seek the advice of a doctor on their own. Other times, family, friends, or co-workers may be ones who must encourage the patient to discuss their drinking habits with their doctor.

Guidelines recommend that primary care doctors routinely screen for alcohol use or dependency during office visits with their patients. Screening may begin with a simple question: “Do you sometimes drink alcoholic beverages?”

Screening Tests for Alcoholism

A doctor who suspects alcohol abuse should ask the patient questions about current and past drinking habits to distinguish low-risk from at-risk (heavy) drinking. Screening tests for alcohol problems in older people should check for possible medical problems or medications that might place them at higher risk for drinking than younger individuals.

A number of short screening tests are available, which people can even take on their own. Because people with alcoholism often deny their problem or otherwise attempt to hide it, the tests are designed to elicit answers related to problems associated with drinking rather than the amount of liquor consumed or other specific drinking habits.

CAGE Test. The CAGE test is an acronym for the following questions and is the quickest test. It asks:

- Have you ever felt you should CUT (C) down on your drinking?

- Have people ANNOYED (A) you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or GUILTY (G) about your drinking

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning, to steady your nerves, or to get rid of a hangover (use of alcohol as an EYE-OPENER [E] in the morning)

Two “yes” responses indicate that the patient is at risk for alcohol dependence.

The CAGE test is more effective for identifying alcohol dependence than alcohol abuse or binge drinking. It is less effective for elderly people than younger people.

AUDIT Test. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)is specifically designed to identify heavy or harmful drinking. It asks three questions about amount and frequency of drinking, three questions about alcohol dependence, and four questions about problems related to alcohol consumption.

Other Screening Tests. Other screening tests are the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST) and the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS).

Ruling out Other Problems

Some symptoms of alcoholism may be blamed on other factors, particularly in the elderly, whose symptoms of confusion, memory loss, or falling may be due to the aging process. Heavy drinkers may be more likely to complain to their doctors about so-called somatization symptoms, which are vague ailments such as joint pain, intestinal problems, or general weakness that have no identifiable physical cause. Such complaints should signal the doctor to follow-up with screening tests for alcoholism.

Tests for Related Medical Problems

Physical Examination. A physical examination and other tests should be performed to uncover any related medical problems.

Laboratory Tests. Tests for alcohol levels in the blood are not useful for diagnosing alcoholism because they reflect consumption at only one point in time and not long-term usage. Certain blood tests, however, may provide biologic markers that suggest medical problems associated with alcoholism or indications of alcohol abuse:

- Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT). This compound is a marker for heavy drinking and can be helpful in monitoring patients for progress towards abstinence. It is the only biologic marker approved by the FDA to help detect chronic heavy drinking.

- Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT). This liver enzyme is very sensitive to alcohol and can be elevated after moderate alcohol intake and in chronic alcoholism.

- Aspartate (AST) and alanine aminotransaminases (ALT). These are liver enzymes and are markers for liver damage.

- Testosterone. Male hormone levels in men with alcoholism may be low.

- Mean corpuscular volume (MCV). This blood test measures the size of red blood cells, which increase in alcoholics with vitamin deficiencies.

Treatment for Alcoholism

There are many options for treatment for alcohol use disorders. They depend in part on the severity of the patient’s drinking.

Treatment options include:

- Behavioral therapy, which may include individual sessions with a health professional and support groups

- Medications

Guidelines encourage primary care doctors to do “brief interventions” to help patients who are alcohol abusers (but who may not yet be alcohol dependent) reduce or stop their drinking. In these interventions, your doctor may give you an action plan for working on your drinking, ask you to keep a daily diary of how much alcohol you consume, and recommend for you target goals for your drinking. If your doctor thinks that you have reached the stage of alcoholism, he or she may recommend anti-craving or aversion medication and also refer you to other health care professionals for substance abuse services.

Overall Treatment Goals

The ideal goal of long-term treatment for alcohol dependence is total abstinence. Patients who achieve total abstinence have better survival rates, mental health, and marriages, and they are more responsible parents and employees than those who continue to drink or relapse. To achieve this, the patient aims to avoid high-risk situations and replace the addictive patterns with healthy behaviors.

Because abstinence is so difficult to attain, however, many professionals choose to treat alcoholism as a chronic disease. In other words, patients should expect and accept relapse but should aim for as long a remission period as possible. Even merely reducing alcohol intake can lower the risk for alcohol-related medical problems.

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and other alcoholism treatment groups express concern about treatment approaches that do not aim for strict abstinence. Many people with alcoholism are eager for any excuse to start drinking again. There is also no way to determine which people can stop after one drink and which ones cannot.

Evidence strongly suggests that seeking total abstinence and avoiding high-risk situations are the optimal goals for people with alcoholism. A strong social network and family support is also important. Families and friends need to be educated on how to assist, and not enable, the drinker. Support groups such as Al-Anon can be very helpful in providing advice and guidance.

Inpatient Versus Outpatient Treatment

Inpatient Treatment. Inpatient care is usually reserved for patients whose alcoholism places them in danger. Inpatient treatment may be performed in a general or psychiatric hospital or in a center dedicated to treatment of alcohol and other substance abuse. Factors that indicate a need for this type of treatment include:

- Coexisting medical or psychiatric disorder

- Delirium tremens (a neurological condition associated with withdrawal that involves uncontrollable trembling, sweating, anxiety, and hallucinations or other symptoms of psychosis)

- Potential harm to self or others

- Failure to respond to conservative treatments

- Disruptive home environment

A typical inpatient regimen may include the following stages:

- A physical and psychiatric work-up for any physical or mental disorders

- Detoxification -- this phase involves initiating abstinence, managing withdrawal symptoms and complications, and ensuring that the patient remains in treatment

- On-going treatment with medications in some cases

- Psychotherapy, usually cognitive behavioral therapy

- An introduction to AA

Some -- but not all -- studies have reported better success rates with inpatient treatment of patients with alcoholism. However, newer studies strongly suggest that alcoholism can be effectively treated in outpatient settings.

Outpatient Treatment. People with mild-to-moderate withdrawal symptoms are usually treated as outpatients. Treatments are similar to those in inpatient situations and include:

- Psychotherapy or counseling

- Medications that target brain chemicals involved in addiction

- Social support groups such as AA

- Cognitive therapies

- Involvement of family and other significant people in patient's life

The current approach to outpatient treatment uses “medical management” -- a disease management approach that is used for chronic illnesses such as diabetes. With medical management, patients receive regular 20-minute sessions with a health care provider. The provider monitors the patient’s medical condition, medication, and alcohol consumption.

After-Care and Work Therapy. After-care uses services to help maintain sobriety. For example, in some cities, sober-living houses provide residences for people who are trying to stay sober. They do not offer formal treatment services, but the people living there offer each other support and maintain an abstinent environment.

Factors That Predict Success or Failure after Treatment

About 25% of people are continuously abstinent following treatment, and another 10% use alcohol moderately and without problems. Relapse is common and intensive and prolonged treatment is important for successful recovery, whether the patient is treated within or outside a treatment center.

Treating People Who Have Both Alcoholism and Health Problems

Severe alcoholism is often complicated by the presence of serious medical illnesses. People with alcohol problems should try to maintain a healthy diet and take vitamin supplements. Nutritional deficiencies are a major cause of health problems in people with alcohol use disorders. Women are particularly at risk.

Treating People Who Have Both Alcoholism and Mental Illness

Treatment for patients with both alcoholism and mental illness is particularly difficult. The greater the psychiatric distress a person is experiencing, the more the person is tempted to drink, particularly in negative situations.

There has been some concern that self-help programs such as AA are not effective for patients with dual diagnoses of mental illness and alcoholism because they focus on addiction, not psychiatric problems. Studies, however, have reported that they can also help many of these patients. (AA may not be as helpful for people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.)

Antidepressants or anti-anxiety medication may help people contending with depression or anxiety disorders. However, in general, these types of medications should be prescribed with caution as they may interact with alcohol. In particular, patients who are currently drinking should never take monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOIs) antidepressants as alcohol can trigger a dangerous spike in blood pressure. People with alcoholism and more severe problems such as schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder may require other types of medications.

Treatment for Alcohol Withdrawal

When a person with alcoholism stops drinking, withdrawal symptoms begin within 6 - 48 hours and peak about 24 - 35 hours after the last drink. During this period, the inhibition of brain activity caused by alcohol is abruptly reversed. Stress hormones are overproduced, and the central nervous system becomes overexcited. Common symptoms include:

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Agitation

- Insomnia

Additional symptoms may include:

- Extremely aggressive behavior

- Fever

- Rapid heartbeat

- Changes in blood pressure (either higher or lower)

- Mental disturbances

- Seizures occur in about 10% of adults during withdrawal. In about 60% of these patients, the seizures are multiple. The time between the first and last seizure is usually 6 hours or less.

- Delirium tremens (DTs) are withdrawal symptoms that become progressively severe and include altered mental states (hallucinations, confusion, severe agitation) or generalized seizures. High fever is common. DTs are potentially fatal. They develop in up to 5% of alcoholic patients, usually 2 - 4 days after the last drink, although it may take 2 or more days to peak.

It is not clear if older people with alcoholism are at higher risk for more severe symptoms than younger patients. However, several studies have indicated that they may suffer more complications during withdrawal, including delirium, falls, and a decreased ability to perform normal activities.

Initial Assessment

Upon entering a hospital due to alcohol withdrawal, patients should be given a physical examination for any injuries or medical conditions. They should be treated, if possible, for any potentially serious problems, such as high blood pressure, anemia, liver damage, or irregular heartbeat.

Treatment for Withdrawal Symptoms

The immediate goal of treatment is to calm the patient as quickly as possible. Patients should be observed for at least 2 hours to determine the severity of withdrawal symptoms. Doctors may use assessment tests, such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA) scale, to help determine treatment and whether the symptoms will progress in severity.

About 95% of people have mild-to-moderate withdrawal symptoms, including agitation, trembling, disturbed sleep, and lack of appetite. In 15 - 20% of people with moderate symptoms, brief seizures and hallucinations may occur, but they do not progress to full-blown delirium tremens. Such patients can often be treated as outpatients. After being examined and observed, the patient is usually sent home with a 4-day supply of anti-anxiety medication, scheduled for follow-up and rehabilitation, and advised to return to the emergency room if withdrawal symptoms increase in severity. If possible, a family member or friend should support the patient through the next few days of withdrawal.

Benzodiazepines. Anti-anxiety drugs known as benzodiazepines inhibit nerve-cell excitability in the brain and are considered to be the treatment of choice. They relieve withdrawal symptoms, help prevent progression to delirium tremens, and reduce the risk for seizures. Long-acting drugs, such as chlordiazepoxide (Librium, generic) or oxazepam (Serax, generic) are preferred. They pose less risk for abuse than the shorter-acting drugs, which include diazepam (Valium, generic), alprazolam (Xanax, generic), and lorazepam (Ativan, generic).

Assessing symptoms frequently and administering benzodiazepine doses as needed (instead of giving a fixed dose at regular intervals) may reduce the incidence of withdrawal symptoms and other adverse events, including delirium, seizures, and transfer to the intensive care unit.

Some doctors question the use of any anti-anxiety medication for mild withdrawal symptoms since these drugs are subject to abuse. Others believe that repeated withdrawal episodes, even mild forms, that are inadequately treated may result in increasingly severe and frequent seizures with possible brain damage. In any case, benzodiazepines are usually not prescribed for more than 2 weeks or administered for more than 3 nights per week. Problems with benzodiazepines include:

- Side Effects. Common side effects of benzodiazepines are daytime drowsiness and a hung-over feeling. In rare cases, they actually cause agitation. Respiratory problems may be worsened. The drugs stimulate eating and can cause weight gain. Benzodiazepines can interact with certain drugs, including cimetidine (Tagamet, generic), antihistamines, and oral contraceptives. Benzodiazepines are potentially dangerous when used in combination with alcohol. Overdoses are serious, although rarely fatal. Elderly people are more susceptible to side effects and should usually start at half the dose prescribed for younger people. Benzodiazepines are associated with birth defects and should not be used by pregnant women or nursing mothers.

- Loss of Effectiveness and Dependence. The main problem with these drugs is their loss of effectiveness over time with continued use at the same dosage. As a result, patients may increase their dosage level to prevent anxiety. Patients then can become dependent. This is a common danger and can occur after as short a time as 3 months. (These drugs do not cause euphoria, a so-called "high," so such drugs are not addictive in the same way narcotics are.)

- Withdrawal Symptoms. People who discontinue benzodiazepines after taking them for even 4 weeks can experience mild rebound symptoms. The longer the drugs are taken and the higher the dose, the more severe the symptoms. They include sleep disturbance and anxiety, which can develop within hours or days after stopping the medication. Some patients experience withdrawal symptoms, including stomach distress, sweating, and insomnia, that can last from 1 - 3 weeks. Sleep changes can persist or months or years after quitting and may be a major factor in relapse.

Antiseizure Medications. Antiseizure drugs, such as carbamazepine (Tegretol, generic) or divalproex sodium (Depakote, generic), may be useful for reducing the requirements of a benzodiazepine. When used by themselves, however, they do not appear to reduce seizures or delirium associated with withdrawal.

Other Supportive Drugs. Beta blockers, such as propranolol (Inderal, generic) and atenolol (Tenormin, generic), are sometimes used in combination with benzodiazepines. They slow heart rate and reduce tremors. They may also reduce cravings.

Specific Treatment for Severe Symptoms

Treating Delirium Tremens. People with symptoms of delirium tremens must be treated immediately because the condition can be fatal. Treatment usually involves intravenous administration of anti-anxiety medications. It is extremely important that fluids be administered. Restraints may be necessary to prevent injury to the patient or to others.

Treating Seizures. Seizures are usually self-limited and treated with a benzodiazepine. Intravenous phenytoin (Dilantin, generic) along with a benzodiazepine may be used in patients who have a history of seizures, who have epilepsy, or in those with ongoing seizures. Because phenytoin may lower blood pressure, the patient's heart should be monitored during treatment.

Psychosis. For hallucinations or extremely aggressive behavior, antipsychotic drugs, particularly haloperidol (Haldol, generic), may be administered. Korsakoff's psychosis (Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome) is caused by severe vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiencies, which cannot be replaced orally. Rapid and immediate injection of the B vitamin thiamin is necessary.

Psychotherapy and Behavioral Methods

Standard forms of therapy for alcoholism include:

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- Combined behavioral intervention

- Interactional group psychotherapy based on the Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) 12-step program

Comparison studies have reported that these approaches are equally effective when the program is competently administered. Specific people may do better with one program than another.

Interactional Group Psychotherapy (Alcoholics Anonymous)

AA, which was founded in 1935, is an excellent example of interactional group psychotherapy. It remains the most well-known program for helping people with alcoholism. AA offers a very strong support network using group meetings open 7 days a week in locations all over the world. A buddy system, group understanding of alcoholism, and forgiveness for relapses are AA's standard methods for building self-worth and alleviating feelings of isolation.

AA's 12-step approach to recovery includes a spiritual component that might deter people who lack religious convictions. AA emphasizes that the "higher power" component of its program need not refer to any specific belief system. Associated membership programs, Al-Anon and Alateen, offer help for family members and friends.

The 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous

- We admit we were powerless over alcohol -- that our lives have become unmanageable.

- We have come to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

- We have made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God, as we understand what this Power is.

- We have made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

- We have admitted to God, to ourselves and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

- We are entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- We have humbly asked God to remove our shortcomings.

- We have made a list of all persons we had harmed and have become willing to make amends to them all.

- We have made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

- We have continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

- We have sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understand what this higher Power is, praying only for knowledge of God's will for us and the power to carry that out.

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we have tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) uses a structured teaching approach and may be better than AA for people with severe alcoholism. Patients are given instruction and homework assignments intended to improve their ability to cope with basic living situations, control their behavior, and change the way they think about drinking. The following are examples of approaches:

- Patients might write a history of their drinking experiences and describe what they consider to be risky situations.

- They are then assigned activities to help them cope when exposed to "cues" (places or circumstances that trigger their desire to drink).

- Patients may also be given tasks that are designed to replace drinking. An interesting and successful example of such a program was one that enlisted patients in a softball team. This gave them the opportunity to practice coping skills, develop supportive relationships, and engage in healthy alternative activities.

CBT may be especially effective when used in combination with opioid antagonists, such as naltrexone. CBT that addresses alcoholism and depression also may be an important treatment for patients with both conditions.

Combined Behavioral Intervention

Combined behavioral intervention (CBI) is a newer form of therapy that uses special counseling techniques to help motivate people with alcoholism to change their drinking behavior. CBI combines elements from other psychotherapy treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement therapy, and 12-step programs. Patients are taught how to cope with drinking triggers. Patients also learn strategies for refusing alcohol so that they can achieve and maintain abstinence. In a well-designed study, CBI -- combined with regular doctor’s office visits (medical management) -- worked as well as naltrexone in successfully treating alcoholism.

Behavioral Therapies for Partners

Partners of people with alcoholism can also benefit from behavioral approaches that help them cope with their mate. Children of an alcoholic mother or father may do better if both parents participate in couples-based therapy, rather than just treating the parent with alcoholism.

Treating Sleep Disturbances

Nearly all patients who are alcohol dependent suffer from insomnia and sleep problems, which can last months to years after abstinence. Sleep disturbances may even be important factors in relapse. Available therapies include sleep hygiene, bright light therapy, meditation, relaxation methods, and other nondrug approaches. Many of the medications for insomnia are not recommended for people with alcoholism. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #27: Insomnia.]

Alternative Methods

Some people try alternative methods, such as acupuncture or hypnosis. Such approaches are not harmful, although it is not clear if they are actually beneficial. In one study, acupuncture reduced the desire for alcohol in nearly half of people, although it was not significantly more helpful than conventional treatments.

Medications

In the U.S., three drugs are specifically approved to treat alcohol dependence:

- Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, generic)

- Acamprosate (Campral)

- Disulfiram (Antabuse)

Naltrexone and acamprosate are categorized as anticraving drugs. Disulfiram is an aversion drug. Other types of medications, such as antidepressants, may also be used to treat patients with alcoholism.

Anticraving Medications

Anticraving drugs are opioid antagonists. These drugs reduce the intoxicating effects of alcohol and the urge to drink.

Naltrexone. Naltrexone (ReVia, Vivitrol, generic) is approved for the treatment of alcoholism and helps reduce alcohol dependence in the short term for people with moderate-to-severe alcohol dependency. ReVia, a pill that is taken daily by mouth, is the oral form of this medication. Vivitrol is a once-a-month injectable form of naltrexone.

Naltrexone should be prescribed along with psychotherapy or other supportive medical management. The most common side effects are nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain, which are usually mild and temporary. Other side effects include headache and fatigue. High doses can cause liver damage. The drug should not be given to anyone who has used narcotics within 7 - 10 days.

It is important that patients take the pill form of naltrexone (Revia, generic) on a daily basis. Because many patients have difficulty sticking to this daily regimen, a monthly injection of Vivitrol may be an easier option. However, some patients suffer adverse injection-site reactions, including spreading skin infections and abscesses. Patients should monitor the injection site for pain, swelling, tenderness, bruising, or redness and contact their doctors if these symptoms do not improve within 2 weeks.

Naltrexone does not work in all patients. Some studies suggest that people with a specific genetic variant may respond better to the drug than those without the gene.

Research is being conducted on the effects of combining naltrexone with acamprosate (Campral), particularly for individuals who have not responded to single drug treatment.

Acamprosate. Acamprosate (Campral) is the newest drug to be approved for treatment of alcoholism. Acamprosate calms the brain and reduces cravings by inhibiting the transmission of the neurotransmitter gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). Studies indicate that it reduces the frequency of drinking and, in combination with psychotherapy, improves quality of life even in patients with severe alcohol dependence. The drug may cause occasional diarrhea and headache. It also can impair certain memory functions but does not alter short-term working memory or mood. People with kidney problems should use acamprosate cautiously. For some patients, combination therapy with naltrexone or disulfiram may provide greater benefit than acamprosate alone.

Aversion Medications

Disulfiram. Some drugs have properties that interact with alcohol to produce distressing side effects. Disulfiram (Antabuse) causes flushing, headache, nausea, and vomiting if a person drinks alcohol while taking the drug. The symptoms can be triggered after drinking half a glass of wine or half a shot of liquor and may last from half an hour to 2 hours, depending on dosage of the drug and the amount of alcohol consumed. One dose of disulfiram is usually effective for 1 - 2 weeks. Overdose can be dangerous, causing low blood pressure, chest pain, shortness of breath, and even death. The drug is more effective if patients have family or social support, including AA "buddies," who are close by and vigilant to ensure that they take it.

Other Drugs

Topiramate. Topiramate (Topamax, generic) is an anti-seizure drug used to treat epilepsy. It also helps control impulsivity. Studies indicate it may help treat alcohol dependence. In one well-designed study, patients who took topirimate had fewer heavy drinking days, fewer drinks per day, and more continuous days of abstinence than patients who received placebo. Side effects included burning and itching skin sensations, change in taste sensation, loss of appetite, and difficulty concentrating.

Baclofen. Baclofen (Lioresal, generic) is a muscle relaxant and antispasmodic drug. It is being investigated for its benefits in helping maintain abstinence, particularly in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis.

Resources

- http://rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov -- Rethinking Drinking: Alcohol and Your Health

- www.ncadd.org -- National Council on Alcoholism

- www.alcoholics-anonymous.org -- Alcoholics Anonymous

- www.al-anon-alateen.org -- Al-Anon Family Group Headquarters

- www.nofas.org -- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

References

Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007 Dec 8;370(9603):1915-22.

Amato L, Minozzi S, Davoli M. Efficacy and safety of pharmacological interventions for the treatment of the Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jun 15;(6):CD008537.

Anton RF. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2008 Aug 14;359(7):715-21.

Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 May 3;295(17):2003-17.

Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011 May;106(5):906-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03351.x. Epub 2011 Mar 7.

Cayley WE Jr. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Mar 1;79(5):370-1.

Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006 Jul;160(7):739-46.

Johnson BA. Medication treatment of different types of alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;167(6):630-9.

Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, Wiegand F, Mao L, Beyers K, et al. Improvement of physical health and quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals with topiramate treatment: US multisite randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jun 9;168(11):1188-99.

Kleber HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF Jr, George TP, Greenfield SF, Kosten TR, et al. Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Apr;164(4 Suppl):5-123.

Lejoyeux M, Lehert P. Alcohol-use disorders and depression: results from individual patient data meta-analysis of the acamprosate-controlled studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011 Jan-Feb;46(1):61-7. Epub 2010 Nov 30.

McKenna W. Diseases of the myocardium and endocardium. In: Goldman L and Ausiello DA, eds. Cecil Medicine. 23rd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: chap 59.

[No authors listed] In the clinic. Alcohol use. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Mar 3;150(5):ITC3-1-ITC3-15; quiz ITC3-16.

O'Connor PG. Alcohol abuse and dependence. In: Goldman L and Ausiello DA, eds. Cecil Medicine. 23rd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007: chap 31.

O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ; Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51(1):307-28.

Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, Lehert P, Vecchi S, Soyka M. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD004332.

Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009 Feb 7;373(9662):492-501. Epub 2009 Jan 23.

|

Review Date:

2/8/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |